Research

Research

Cancer is thought to arise from the accumulation of genetic mutations that causes cells to acquire several characteristics, such as uncontrolled proliferation, immortality, and invasiveness. There are many oncogenic gene mutations that have been identified in previous studies. It has also been shown that, however, there is a number of cells carrying such oncogenic mutations in our body that do not actually show carcinogenesis, and that the number and types of such mutant cells increase over the years.

Then, what is the trigger for carcinogenesis by which those cells harboring oncogenic mutations evolve into malignant tumors? Are there inevitabilities that trigger carcinogenesis, rather than just an accidental accumulation of mutations?

Based on this idea, our laboratory is exploring "inevitabilities that are not governed by chance in the process of cancer cell evolution in living tissues".

Using Drosophila melanogaster (Fruit fly) as an experimental model, we are currently studying the tissue-intrinsic tumor invasion niche (Invasion Hotspots), collective invasion, polyploid cancer cells (PCCs), and cooperative cellular interactions in cancer cell evolution.

We discovered the following phenotypes of oncogenic mutant cells in the Drosophila larval tissues (wing imaginal epithelia) using genetically mosaic techniques.

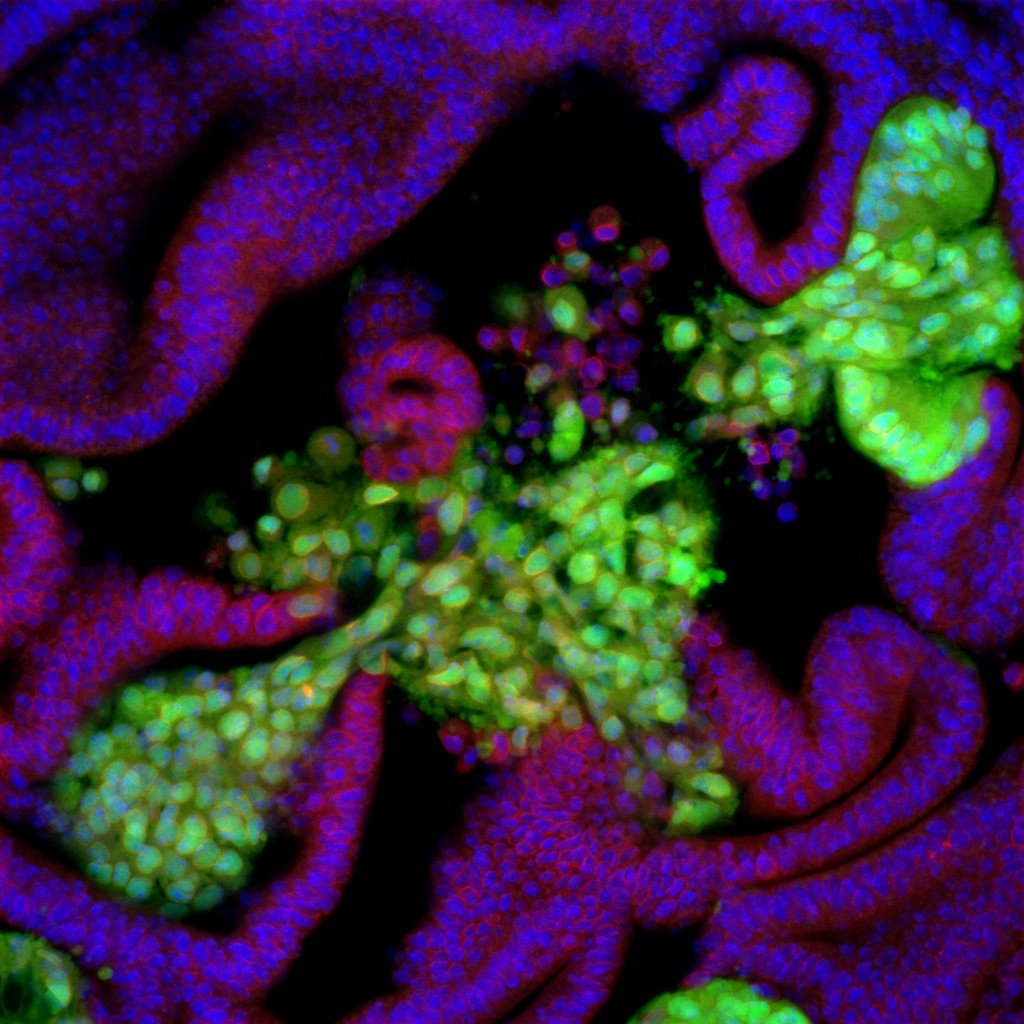

Oncogenic mutant cells formed tumors that break through the underlying basement membrane and begin to invade the extracellular matrix from several specific spots (invasion hotspots) in the epithelial tissue with a very high probability.

Oncogenic mutant cells that are induced outside of the invasion hotspots do not break through the basement membrane and grow into benign tumors on the luminal side, even though they carry the same genetic mutations.

Some of the tumor cells that show invasive behaviors undergo polyploidization by endoreplication.

Focusing on these phenomena, we are investigating the conditions underlying invasion hotspots, the triggers for polyploidy through endoreplication, and the functional relationship between polyploidy and tumor invasion. We are also studying whether similar phenomena can be observed in other experimental models (mice, mammalian cultured cells) and even in actual human pathological tissues.

Polyploid Cancer Cell Models in Drosophila. Wang, Y. and Tamori, Y. Genes (2024), 15(1), 96.

The initial stage of tumorigenesis in Drosophila epithelial tissues. Tamori, Y. Advances in Experimental Medicine and Biology (2019), 1167: 87–103.

Cell Competition and tissue homeostasis through compensatory cellular growth. Tamori, Y. and Fujita, Y. Journal of Japanese Biochemical Society (2019), 9: 147-158. (Japanese).

Invasion Hotspots

Invasion Hotspots

Carcinogenesis is understood as a stochastic process in which mutations in multiple genes, including oncogenes and tumor suppressor genes, accumulate over time, causing what was originally a normal cell to acquire new characteristics and evolve into a cancer cell. In fact, cells mutant for one type of tumor suppressor gene that appear in epithelial tissues are outcompeted by the surrounding normal cells and rarely lead to tumor formation, but when another oncogenic mutation is introduced into the mutant cells, they begin to overproliferate and invade other tissues. Such early events of carcinogenesis in vivo have been demonstrated by genetic experiments using model organisms such as Drosophila melanogaster.

Our previous studies, however, have shown that most of the multiple mutant cells, even those with strong oncogenic properties, proliferate in the epithelial layer toward the luminal side and form benign tumors. At the same time, the multiple mutant cells break the basement membrane and invade the stroma only when they appear at specific locations in the epithelial tissue. In addition, even with only one type of oncogenic mutation, mutant cells that emerged in the specific locations showed similar invasive phenotypes. This finding suggests that not only genetic mutations but also the tissue-intrinsic local microenvironment play a decisive role in the carcinogenic process.

We found that, in these tumor invasion niches that we dubbed "invasion hotspots," there is a slight distortion in the intrinsic cellular arrangement and polarity. This finding led us to hypothesize that this structural distortion makes the spots vulnerable to tumorigenic stimuli and that these spots tend to be the starting point for tumor invasion. We are currently conducting a thorough analysis of the morphological, structural-dynamic, and genetic characteristics of the invasion hotspots to identify the factors that characterize the spots. We are also studying the role of this structure in development and the reason why cancer cells start their invasion from the spots.

Tumor-Cell Invasion Initiates at Invasion Hotspots, an Epithelial Tissue-Intrinsic Microenvironment. Kobayashi, R., Takishima H., Deng, S., Fujita, Y. and Tamori, Y. bioRχiv. 2021.09.28.462102

Tumor hotspots: Tissue-intrinsic oncogenic niche. Kobayashi, R. and Tamori, Y. The Cell (Saibo), “Angiogenesis and immunity in tumor development” (Japanese).

Tissue-intrinsic tumor hotspots: terroir for tumorigenesis. Tamori, Y. and Deng, W.-M. Trends in Cancer (2017), 3: 259–268.

Epithelial tumors originate in tumor hotspots, a tissue-intrinsic microenvironment. Tamori, Y., Suzuki, E. and Deng, W.-M. PLoS Biology (2016), 14(9): e1002537.

Polyploid cancer Cells

Polyploid cancer Cells

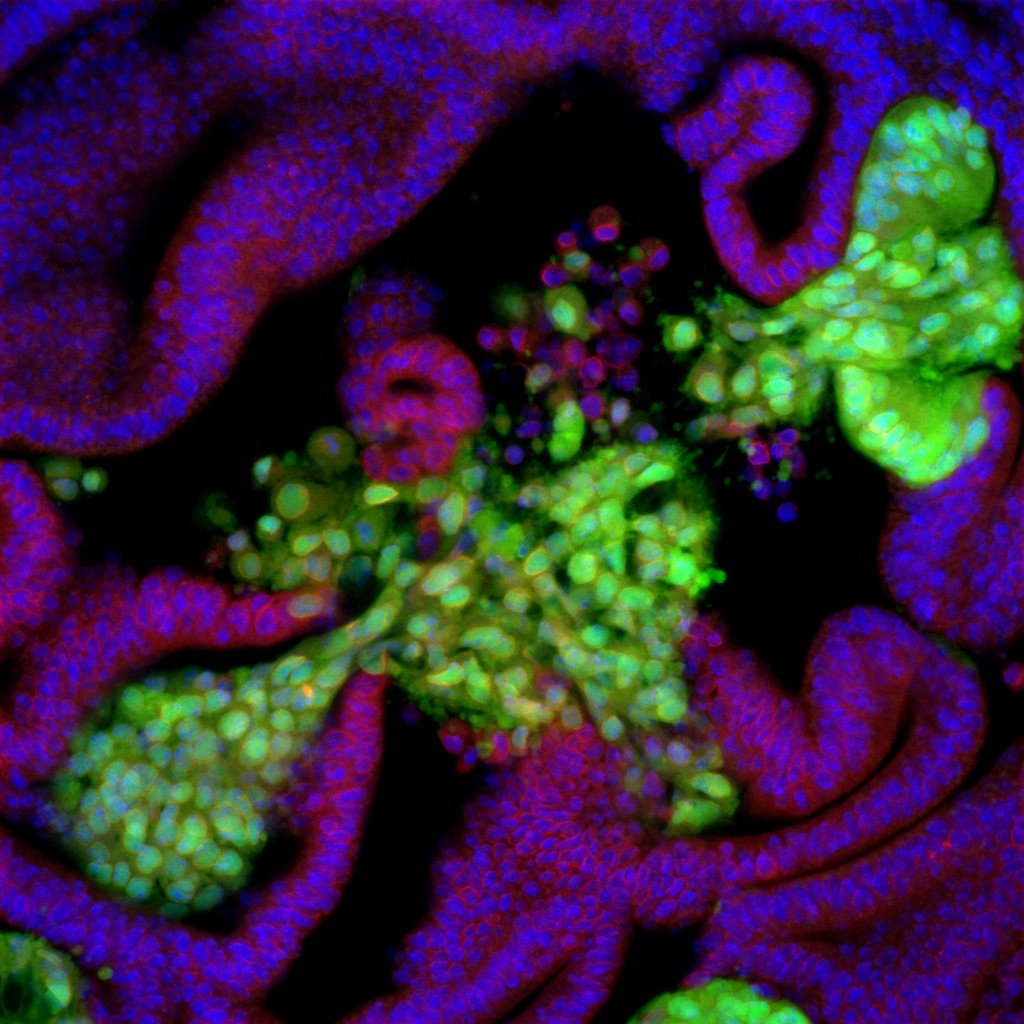

Malignant tumor tissues contain a highly heterogeneous mixture of various mutant cells with different genetic backgrounds, and many reports indicate that interactions and competition among these heterogeneous cells have an important role in cancer progression. It is known that, within this diverse cancer cell population, polyploid cancer cells in which ploidy increases from normal diploidy to tetraploidy or more are often observed.

Polyploid cells are highly resistant to various stresses such as radiation and mitotic inhibitors, and it has been shown that the mitosis of polyploid cells tends to produce a variety of aneuploid daughter cells, which may play an important role in the process of cancer cell evolution. However, the nature of this process is not well understood due to the lack of appropriate experimental models.

In our studies using Drosophila, mouse, and mammalian cultured cells, we have found that under certain environmental conditions, some types of oncogenic mutant cells stop normal mitosis and become polyploid by entering an endoreplication cycle. These data suggest that this polyploidization of tumor cells is not caused by an accidental error during cell division but by the mitotic-to-endocycle transition and that this phenomenon inevitably occurs when conditions are met in a local tissue environment. In our tumor models, furthermore, we found that invasive cells emerge from these polyploid cells, leading us to study the ploidy dynamics in carcinogenesis and the evolution of malignant traits starting from the polyploid cells.

Polyploid Cancer Cell Models in Drosophila. Wang, Y. and Tamori, Y. Genes (2024), 15(1), 96.

Compensatory cellular hypertrophy

Compensatory cellular hypertrophy

Polyploidization of the genome can be observed as a genetically programmed process in the development of multicellular organisms. In Drosophila, the developmental polyploidization in some tissues such as larval salivary glands or ovarian follicular epithelia has been intensely studied as a research model for chromosomal dynamics and cell cycle regulation for a long time. Such polyploidization is programmed to produce large amounts of specific proteins in each tissue and can be seen also in human cells such as placental trophoblasts, hepatocytes, and cardiomyocytes. Although polyploid cells are often observed in aged or cancerous tissues, these polyploidizations are thought to be accidental, caused by gene mutations, or abnormalities in cell division.

Our previous studies have discovered a phenomenon called "compensatory cellular hypertrophy (CCH)" by which an abrupt cell death and a local cell loss in postmitotic tissues are compensated through polyploidization-induced cellular hypertrophic growth without cell division. Furthermore, our genetic experiments using Drosophila follicular epithelia revealed that, in the CCH, physical stretching stress induced by loss of local tissue volume triggers polyploidization of cells in the surrounding area. Similar phenomena have been successively reported not only in other tissues of Drosophila but also in various tissues of vertebrates including human (liver, corneal endothelium, renal tubules, epicardium, etc.). Therefore, CCH can be considered a widely conserved tissue repair system in postmitotic tissues.

Mechanotransduction-mediated epithelial tissue repair through cell competition. Nara, S. and Tamori, Y. Journal of Clinical and Experimental Medicine (Igaku No Ayumi) (2020), 274: 434–441. (Japanese).

Growth of winner cells in cell competition - replacement and compensation. Tamori, Y. Journal of Clinical and Experimental Medicine (Igaku No Ayumi) (2016), Vol. 29, No. 9 (Japanese).

Compensatory tissue repair in cell competition. Tamori, Y. Seitai No Kagaku (2016), Vol. 67, No. 2 (Japanese).

Compensatory cellular hypertrophy: the other strategy for tissue homeostasis. Tamori, Y. and Deng, W.-M. Trends in Cell Biology (2014), 24, 230–237.

Tissue repair through cell competition and compensatory cellular hypertrophy in postmitotic epithelia. Tamori, Y. and Deng, W.-M. Developmental Cell (2013), 25, 350–363.